The Underground Meets the Art World: Berlin Atonal 2025

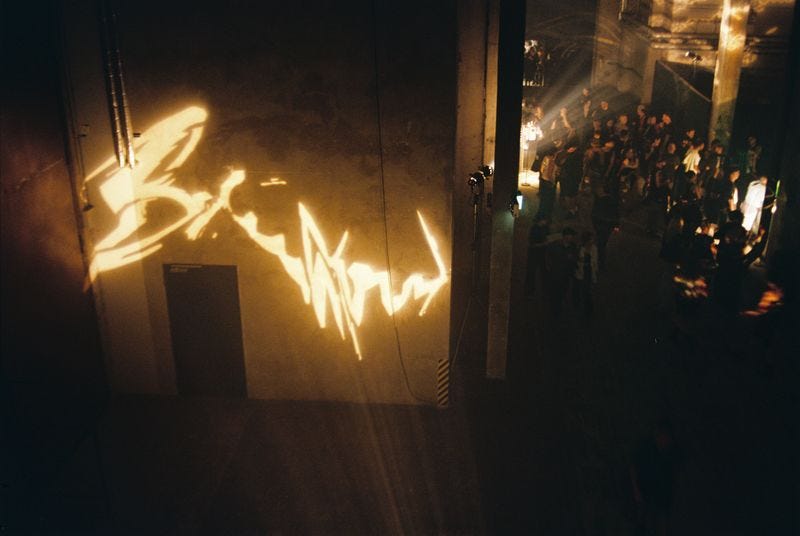

Berlin Atonal is underground music on a grand canvas; underground music scaled way the fuck up. No longer is this twenty-or-so t-shirted reprobates in a fire-hazard backroom (RIP Loophole): it’s dress-to-impress, glossy brochures and programme essays and thousands of people—locals and tourists, young and old—in a Tate Modern-esque renovated power station with several distinct venues (two live stages in Kraftwerk, cinema and video game spaces, art installations, as well as Ohm, Globus, Tresor) and a labyrinth of dark passages connecting it all.

‘I wanted to bring Woodstock to my village,’ Dimitri Hegemann once said of his early aims as a countercultural tyro, his village being in North Rhine-Westphalia. Relocating to West Berlin in 1982 after musicology studies, the future Tresor-creator founded Atonal as a festival of experimental music, which brought to West Berlin underground acts like Coil, Psychic TV and the early Jeff Mills project Final Cut.

Later (my favourite Hegemann trivia) he brought Timothy Leary to Berlin, arranging for Leary to give a guest lecture on psychedelia and cybernetics in 1990 at the Humboldt University. Apparently, sheltered from decadent Western culture, the university authorities didn’t know who Leary was, approving the lecture as being from a visiting Harvard-affiliated psychiatrist rather than from the LSD guru who’d led millions of young people to drop out.

Now the scene’s benevolent Opa, Hegemann has handed over the Atonal brand to younger programmers (Laurens von Oswald and Harry Glass) to run it in his enormous Kraftwerk/Tresor complex. They’ve done an outstanding job by any measure, something I told them in person late one night years ago when they crashed a party in a WG where I was living, to which they showed up in a . . . merry mood. Merry is far from how I’d describe Atonal’s altogether serious branding, something I’ll get back to.

Now a biennale, this year’s festival ran over six nights. I attended on the opening Wednesday and the Friday, regretably missing all sorts of good stuff on the other nights (like Chuquimamani-Condori).

As I walked around the power station ground floor early on Wednesday looking for music, all over the dark, concrete walls were posters from contemporary artists (Mouneer Al Shaarani and Roberto Cuoghi), fly-poster-style, poking fun at white privilege and Western liberals’ smug complacency.

Nearby, a performance art installation by Kristoffer Akselbo had a man coming in and out of a wooden hut, wearing a grotesque facemask, tending to some plants (Voltaire’s ‘Il faut cultiver notre jardin’ stoicism was the only thing I could think of to try to make sense of it).

The first music I heard was the wonderful contemporary post-jazz trio Ghosted (the prefix ‘post’ often saves the day when you’re trying to put a genre tag on these musics). Over looped double-bass lines (Johan Berthling), guitar (Oren Ambarchi) squawled and frazzled, while the drums subtly shuffled and grooved (Andreas Werliin). It was a bit like the Necks, but further out.

The new stage-cum-art area where Ghosted played, with seating and moody lighting and whatnot, is called the Third Surface. You get a sense of Atonal’s artspeak approach from the fact that the Third Surface wasn’t allowed to exist without a theory-propelled programme note of its own: ‘a newly conceived audience environment inspired by the informal spaces and counter-institutions of nightlife before the rise of dance music. Here, music and artworks create the framework for new types of social and psychic assembly.’ If you know what a psychic assembly is, do let me know. Moreover, ‘The works shown act not as declarations but as cues.’ OK.

Carmen Villain opened the main stage, up a few staircases on the third floor. Walking into the Kraftwerk upstairs space is (cliché alert!) like entering an industrial cathedral, this huge carefully lit ruin vaulting high into the hazy distance. It’s sublime ruin porn, urban decay writ large as a kind of realness-retreat from the fakeness of everyday life. Villain’s set brilliantly mixed raster-style glitch-pulses with the gargantuan reverb of the Kraftwerk main space, with adornments by Norwegian flautist Johanna Orellana and trumpeter Eivind Lønning.

Contemplative and evocative, NYX combined operatic female solo vocals and choral polyphony with at-times overwrought melodramatic violin. After, Lee Ranaldo, Peder Mannerfelt and Yonatan Gat, with Leah Singer providing colourful projected visuals, playing a freaky Beat-generation-improv-style set, replete with spoken word and harmonica abuse, recalling the million Sonic Youth gigs I enjoyed in my own youth.

Closing the main stage on the first night was Bendik Giske (tenor saxophone) and Sam Barker (electronics). Though I only caught a bit of them, their ambient synth pads with loooooong reverrrrrrrrberated saxophone was giving lush cyberpunk noir, building on Barker’s ECM-friendly album Stochastic Drift from earlier this year.

Noise music was to the fore on the Friday night main stage. After the meditative palette-whetting intro of artist Nicolas Mangan’s Core Correlations (which, as Atonal likes to do, blurred the lines between contemporary art and music), bela took to the stage for her solo performance. And though I say solo, wow, was she legion.

Performing a piece called Korean Love Sonnets with scenography by Anton Filatov, dressed in a white robe, solitary in front of hundreds of eyes high in this power station, bela first spoke a few unassuming words, then launched into excoriating avant-garde noise. Beginning with deep heavy metal voice over clanging percussion samples, she eventually built up over an hour to horror-movie-style screaming. On the way, she walked through the crowd holding aloft two bells, resonating them like a Roman Catholic priest.

Bela’s was the most impressive performance of the Friday, and, notwithstanding their quality, the later noise acts—RIEND (Puce Mary and Rainy Miller) and Lord Spikeheart—didn’t so much grab me, as, when it comes to noise, my ear quickly goes dead from the lack of harmonic interest.

Refreshingly—daringly, even—Atonal was a German art event that wasn’t genocide-denying (imagine saying those words ten years ago). Bendik Giske wore a ‘FREE GAZA’ message on his clothes. And when I returned for the Friday night, I made a beeline for the cinema room, which was supposed to be showing O, Persecuted by Basma Al-Sharif, a film based on a restoration of Palestinian militant film Our Small Houses. This was one of three Palestinian films programmed over the six evenings. Overall, Global South perspectives were present throughout the space, such as Tanja Al Kayyali’s embroidered work The Moon.

One of the fascinating things was the demographic divisions—tribal divisions, almost—between spaces. Upstairs in Kraftwerk, while DJ Marcella was playing a deliriously genre-defiant set to a crowd of older avant-weirdos (long may they endure!) quenching their thirst for delirium, downstairs in Globus and Tresor, Djrum was doing something similar (ingenious genre-bending DJ madness) to mostly younger clubbers and tourists, getting off their faces. Parents upstairs, kids downstairs.

Ohm was the intermediate space and where some of the best music was heard. NVST created a propulsive stream of hyped-up beats, DnB and IDM and Hyperpop. Wrecked Lightship (Appleblim and Winchester) went deep for a set of Leviathan psych-dub, building up over the course of an hour before dropping to a woozy lighters-in-the-air sunset. Their albums Antiposition and Drained Strands contain some of my favourite bass music of recent years.

In the Third Space, YHWH Nailgun mesmerised with their psychedelic post-hardcore. Guitar didn’t sound like guitar; drums didn’t sound like drums; voice didn’t sound like voice; synth didn’t sound like synth. All was well. We danced in different time signatures.

If I’m being super critical, there was at times a slight bit of stylistic homogeneity, and noticeably, too few live bands. I don’t know whether rowdy bands and singers are too déclassé for the curatorial contemporary art vision, but RnB is at the roots of all unpopular music, and I would have liked to have the opportunity to vibe to more drumkits.

Looking at the roster of artists who appeared in the Kraftwerk space, several of them come from one booking agency, Outer, which was co-founded by Atonal’s co-director Laurens von Oswald. There will always be a local tinge to festivals (as there should be), but maybe looking further afield for live bands will be worthwhile for 2027’s edition. I’d love to see someone like Kirin J Callinan at the next one, or black metal, or in general more irreverence.

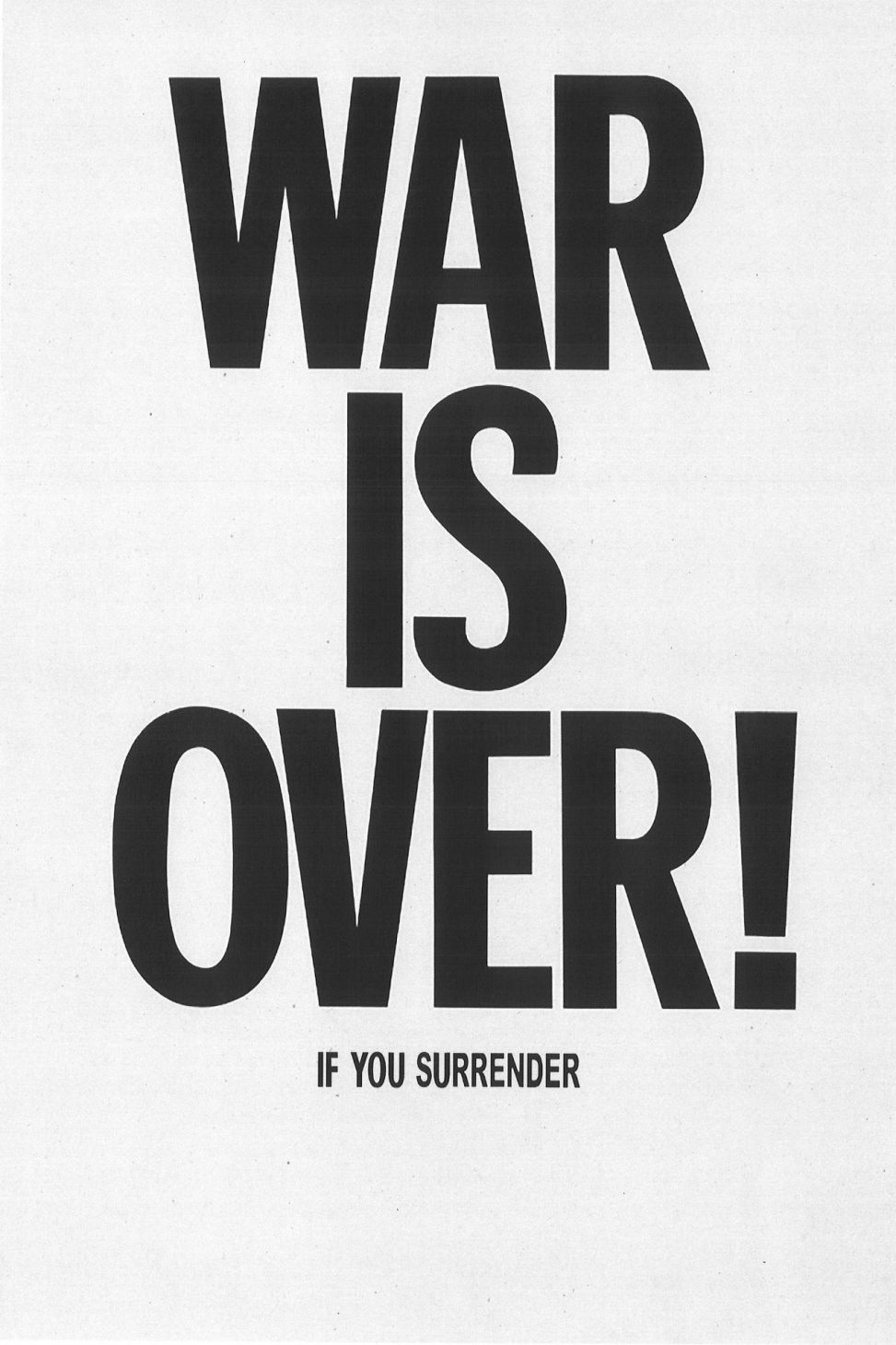

A big part of 1980s and 1990s underground music culture was zines and DIY stuff. Those zines would be Xeroxed and feature all sorts of scurrilous nonsense with misspellings and text jostling with image. A genuine alternative to the mainstream, they would take the piss out of you and out of everyone else. Think Raymond Pettibon’s covers for Black Flag and the like. When the underground gets scaled up, does humour have to make way for respectable artspeak? I really hope not. Satire has always been one of the underground’s antidotes to the everyday world’s dullness and hypocrisy.

A few years ago, Simon Reynolds coined the term Conceptronica for ambitious, high-concept electronic music at the intersection of festivals, galleries and gigs. Reynolds was highlighting recent music with a long theoretical explanation behind it, speaking the language of contemporary art curators, often benefitting from arts funding. Atonal was full of that kind of thing, and I share Reynolds’ ambivalence. There should be no underground without the G. G. Allins, so to speak. Excess, waste, filth and funniness are by definition irrecuperable, avoiding conceptualisation, and they’re the flowers that crack concrete.

Criticism over. Thank God for Atonal. It was life-affirming. It was fun. It made me think of what underground music is in 2025. And it made me grateful to live in Berlin—no mean feat at the moment. Hegemann bringing Leary to Berlin gives us a throughline from the 1960s US counterculture to the 1990s-and-beyond Berlin counterculture. I’m grateful that thread still exists, that I’m woven in it, and that Atonal’s current custodians have their heads screwed on. Keep Berlin weird.